Small-scale geothermal power development in Japan – insights from Machiokoshi

Shoji Numata, President of Machiokoshi Energy, provides some insights on the trend of developing small-scale geothermal power facilities in Japan.

In an interview published by Nikkei Business Publications, Shoji Numata, President of renewable power developer Machiokoshi Energy, gave valuable insight on why the trend of geothermal development in Japan has seemingly focused on small-scale power projects.

A country update published by the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC) in 2023 showed that Japan currently has the highest density of geothermal power plants in the world. An important qualifier is that most of these power plants are considered small, with capacities ranging from 20 to 250 kW.

Machiokoshi Energy is seemingly following this trend with the construction of the 5-MW Oguni geothermal power plant in the town of Oguni in the Kumamoto Prefecture. The company is unique in that it was founded by Shoji Numata, a supermarket mogul who envisions bringing a “franchise” model to the geothermal business. Aside from focusing on small-scale development, Machiokoshi packages the geothermal projects as vehicles for multipurpose community economic revitalization. This means that the projects can provide opportunities beyond power production.

Small projects shorten the development time

Commenting on the trend of small-scale geothermal power development, Numata explained that the strategy significantly shortens the development time of geothermal power projects. “Most existing geothermal power plants take more than 15 years to start operation. For private companies, dedicating personnel for such a long period of time before operation is a huge burden,” he explains.

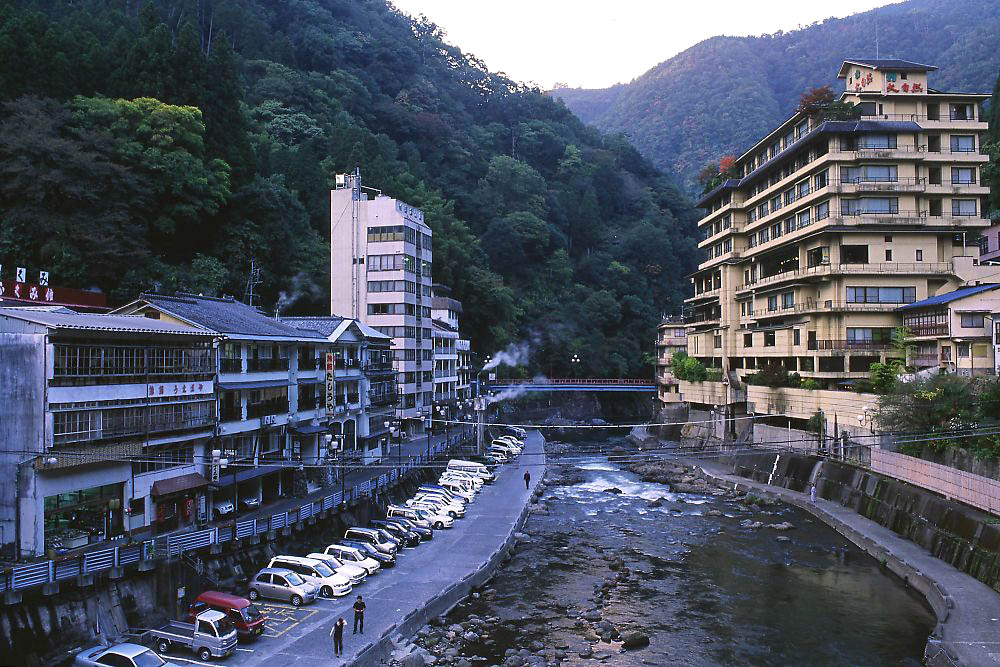

The fact that many sites are located within national parks and potentially coincide with operations of the hot spring industry also adds another layer of complexity to developing geothermal projects.

For the Oguni geothermal power project, the decision to limit the size to 5-MW significantly simplified the process. Instead of custom-made designs for the power plant, the company relied on a basic design that can be manufactured and deployed quickly.

Numata further explains that environmental assessment of projects with a planned output of 7.5 MWe or more can take between 2 to 4 years. It can then take an additional 2 years for the design and manufacture of power plant equipment. This adds on to the approximately 10 years it takes to explore and evaluate the surface and subsurface characteristics of a potential project site.

However, Numata remains steadfast in support of geothermal in Japan. “Japan is not blessed with fossil fuel resources, but it is said to have the third highest potential in the world when it comes to geothermal energy. It is a stable source of power that we can be proud of.”

“As a Japanese company involved in renewable energy, we wonder what we are doing if we don’t get serious about geothermal power.”

“If it doesn’t exist, make it yourself”

Numata draws on his experience in the manufacturing and retail industry to carry the “making what does not exist” philosophy to geothermal. An example of this is the small, crawler-type drilling rig and mobile steam separator that the company designed in-house. This allows for drilling of geothermal boreholes up to 1 kilometer deep, even when there are no roads leading to the project sites.

This type of innovation not only shortened project development time, but also reduced costs significantly. “With the conventional tower method, the excavation cost for one hole would run into the hundreds of millions of yen, but with this method it only cost a few tens of millions of yen,” said Numata.

Numata also established Geopower Academy, a vocation school for drilling in Hokkaido. The institution aims to bridge the competency gap left by the lack of institutional support for geothermal in Japan in the 1990s.

Source: Nikkei Business Publications